Part 2 of this series is focused on the Tennessee Association of School Librarians’ banned books campaign.

The Tennessee Association of School Librarians (TASL) “Banned Books Week” campaign is coming to schools beginning September 18th. Self-described activist school librarians will dare students to “rebel” by reading an so-called “banned book”. Updated AASL (American Association of School Librarians) national school library standards adopted by TASL, endorse banned book lesson plans and displays in schools.

Murfreesboro, TN

The three-tiered library organizations’ “Banned Books Campaign”

Under the guise of “celebrating the freedom to read”, the ALA (American Library Association), the AASL, and TASL push the “banned books week” campaign as part of a political agenda generally described as a “left-of-center approach to public policy”.

Led by the ALA which co-launched the banned books campaign, library associations have been pushing the banned books campaign for 50 years and have helped spread its popularity to bookstores and schools. Restrictions applicable to digital collections are under attack as well.

The “banned books” campaign is based on what the ALA ’s Office of Intellectual Freedom (OIF), deems “censorship” in any form which they say means removing a book from the library collection or in the case of “soft censorship”, restricting access to a book. TASL has likewise taken a forthright stand on censorship of books in school libraries.

It is not censorship, however, when a librarian declines to add certain materials to the library’s book collection. Nor was it censorship in 2019, when Katherine “Katie” Ishizuka and Ramon Stephen, founders of The Concious Kid, instigated a takedown of Dr. Seuss books based on allegations of racism. Their attack on the books convinced the National Education Association to remove Seuss from the Read Across America annual celebration in schools and instead, shift the focus to “diverse” books including “books about race, gender identity, and various other left-wing causes”.

The following year, Ishizuka was appointed editor-in-chief of the School Library Journal (SLJ).

In a recent SLJ article titled School Librarians Must Lead the Ongoing Conversation About Problematic Titles and Library Collections, Nashville school librarian Erika Long (who also serves as an AASL State Level Leader for TASL), says that when a librarian decides to remove a book it’s “basic [book] collection development”.

As another librarian put it, “[w]henever a book diminishes human beings through harmful stereotypes or racist language or imagery, that book has no business being on a school library bookshelf”.

In other words, librarians decide the which books make it into the library’s book collection and when librarians make value judgments to remove a book, it can’t be censorship because they were taught in school that “there’s pedagogy behind” these decisions.

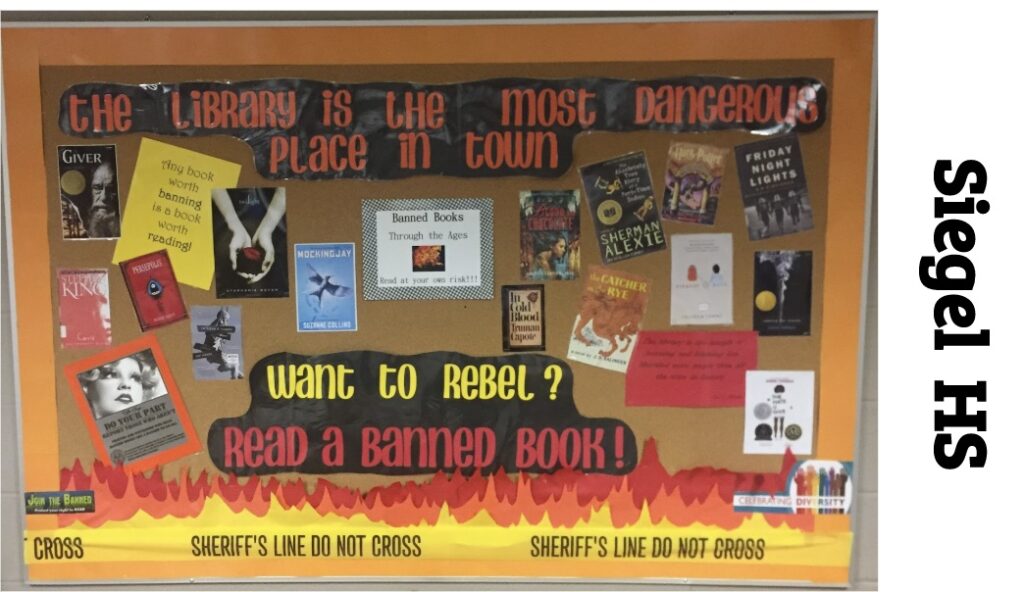

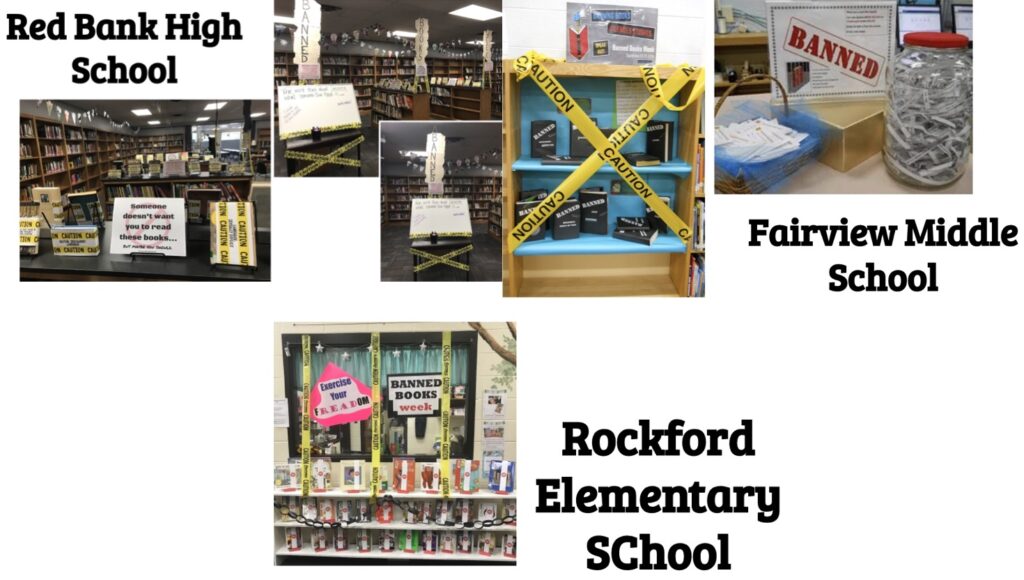

The AASL is enthusiastically pushing “banned books week” out to state chapters like TASL whose website features past banned books displays from elementary, middle and high schools across Tennessee.

The TASL’s September 2022 Conference agenda

TASL’s 2022 annual conference will take place this year a week before ‘banned books week”. Many of the sessions align with the updated AASL Standards adopted by TASL including:

- TASL’s Equity, Diversity, Inclusion (EDI) committee chair Brandi Hartsell, a Knox County school librarian, will speak about how school librarians can influence teachers and shape their “cultural competence” using “diverse books”. Hartsell has written about her program for educators and encourages the use of the AASL manual on Defending Intellectual Freedom: LGBTQ+ Materials in School Libraries.

- “ProjectLit + Ways to Advocate Through Book Clubs” presented by Nashville Cane Ridge high school librarian Tyler Sainato who will describe how she helped students become political activists around perceived anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation. Sainato was featured in a recent School Library Journal article centered around promoting the perceived needs of LGBTQIA+ students, including transgender students in elementary school. (political activism is a target goal of TASL’s advocacy directed at students).

- Tennessee elementary school librarian Caroline Mickey (Alpine Crest Elementary School in Red Bank, TN), will talk about “Being an Ally” and “Activism for Introverts”. Mickey’s posted bio states that, “[s]he has been on a personal mission to expand her horizons and learn about her privileges so that she can acknowledge and work to help others recognize theirs. Caroline was recently quoted in a Washington Post article for standing up to book bans in front of her school board. She had recently become the chair for the EDI [equity, diversity & inclusion] Committee…

”Mickey describes her “Being an Ally” session here -“As educators, we are constantly learning how to better support our students. Our BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ students need to know they are welcome in our spaces, we will respect them, and that their stories will be shared and reflected on the shelves. My presentation dives into librarianship and activism and how we can be there for our students.”

- Three Tennessee school librarians (one from Rutherford County and two from Davidson County), will talk about state law related to school libraries and promote ideas to celebrate “Banned Books Week” in schools.

- Dr. Cindy Welch, Clinical Associate Professor, UTK, School of Info Sciences, will speak about how “[i]ncreased scrutiny and edgier-than-ever diverse and inclusive materials has made it harder – and even hazardous – to do the best job for our children. This session will review related intellectual freedom policies and speak to strategies for stocking elementary school libraries, and continuing the good fight.”

The library associations define “Intellectual freedom” as “the right of every individual to both seek and receive information from all points of view without restriction. It provides for free access to all expressions of ideas through which any and all sides of a question, cause or movement may be explored.”

Defending Intellectual Freedom is the AASL’s guide to assist school librarians using the AASL Standards to help students access LGBTQ+ materials. Along with the activity guide, the AASL provides a detailed chart to support the expansion of LGBTQ+ school library book collections and instruction for students regarding the materials.

The working definition of “intellectual freedom” assumes no information or curation bias on the part of the librarian and that information representing “all sides” on topics such as gun control, legalization of marijuana, abortion and transgenderism, would be easily accessed in the school library. Suggested sources in the “curate” activity guide for students to use to verify information, suggest otherwise.

Similarly, the guide’s suggestion that students use the “ACT UP Method” to validate information should be questioned. As described in the AASL guide, “[t]he primary function of the ACT UP method goes beyond evaluating the credibility of sources. It helps learners to push against privilege and break out of the dominant narrative search cycles”. The “ACT UP” author describes the intent behind the method:

-

- To ACT UP means to act in a way that is different from normal. Normal is defined as heteronormative, white, cisgendered, male and christian (just to name a few). Normal means patriarchy and the systemic oppression of marginalized groups.

- To ACT UP means to actively engage in dismantling oppressions.

- To ACT UP means pushing against dominant narratives, oppressive hierarchies of knowledge production, and academic ivory tower definitions of expertise and scholarship.

The “Banned Books” campaign and the AASL Standards

This year’s “Banned Books Week” theme is “books unite us, censorship divides us”, a theme which fits well with the new AASL Standards.

TASL, Tennessee’s state chapter of the AASL has been training school librarians in the AASL Standards even though these standards have not been adopted by either the Tennessee Department of Education or the State Board of Education. Regardless, the ALA and AASL require that any school librarian preparation program that wants ALA or AASL accreditation “must” use the ALA/AASL school librarian preparation standards which “reflect the ideals and language in the AASL [National School Library] Standards.” In fact, the first school librarians preparation standard requires that the AASL Standards be part of their training.

As explained in Part 1, the AASL Standards are supported by AASL activity guides which are written by teams of ALA “emerging leaders” who are librarians with fewer than five years of experience.

In one activity for example, AASL’s suggestion for school librarians confronting a book challenge is to “facilitate and share lesson plans that incorporate banned books”.

TASL’s current president agrees that school librarians should follow state law as it applies to the Age Appropriate Materials Act which was passed this legislative session. Lindsey Kimery, coordinator of library services for Metro Nashville schools, past president of TASL and chair of the AASL Chapter Delegates, likewise conceded to this bill and is confident that “TASL members do not purchase obscene or pornographic materials for school collections”.

It may, however, depend on whether books currently in Tennessee school libraries like Gender Queer, Lawn Boy and TASL recommended Flamer meet the state law’s definition of obscenity or pornography.

In her May 2022 article posted in the American Libraries Magazine, Kimery tells how members of TASL and TLA “worked nonstop to counter [HB1944] this harmful legislation” which would have made the state’s obscenity law apply to school libraries and possibly result in books which violate the “harmful to minors” law, being removed from the school library.

Kimery is opposed to book bans, “worried that young readers could loose access to ideas and information in their schools” including,“titles written by or about marginalized communities, such as racial minorities or students who identify as LGBTQ”.

Rep. Sam Whitson introduced Kimery in committee to speak in support of his bill to reinstate a state-wide school library coordinator within the Department of Education.

Court rules that removal of book from school library is not a book ban

Inflammatory book ban rhetoric and school displays may get attention from staff and students, but telling the school community that the books are “banned” is misleading at best. For that matter, school administrators and school boards should question the propriety of the school library being used for any library associations’ political campaign. School administrators and school boards should carefully probe claims that students’ rights are violated when books are removed from school libraries.

In C.K.-W. v. Wentzville R-IV School District, an August 2022, federal case filed by the ACLU challenging a Missouri school district’s policies regarding book challenges and the removal of books from a school library, the court held that “[a] school district does not ‘ban’ a book when, ‘through its authorized school board’, it ‘decides not to continue possessing [a] book on its own library shelves”.

Two school board policies were involved in this case; one policy permitted school librarians to remove materials “ based upon the contribution to the education program and the age appropriateness of the materials”, while the other policy permitted a committee to review complaints challenging library materials resulting in possible removal.

Plaintiff C.K., a minor student’s case was filed by her parent, T.K. They claimed that the books, three of which were removed indefinitely violated students’ First Amendment rights “by restricting their access to ideas and information for an improper purpose.”

Law Professor Eugene Volokh, recognized as “one of the nation’s top experts on First Amendment law”, provides an instructive analysis of the case, concluding that as to K-12 public school libraries, “the [court’s] decision seems legally correct to me.”

This case is important for several reasons especially as it relates to Tennessee’s Age Appropriate Materials Act and Public Chapter 1137 (which sets forth the age appropriate standard), and the continued reliance by the three-tiered library associations on the Supreme Court’s case Board of Ed. v. Pico, an earlier school library book removal case also filed by a student. Generally, the library associations cite the Pico case for the proposition in Justice Brennan’s plurality opinion that “school officials can’t ban books in libraries simply because of their content” and that students have a “right to receive ideas [as] a necessary predicate” to the exercise of their First Amendment rights.

What the library associations don’t disclose about the Pico case is that it was not a majority opinion and as Volokh points out the decision has no real value as legal precedent.

According the most generous reading of the Pico case as it applies to a student’s First Amendment right to “receive ideas”, Volokh concludes that the takeaway from Justice Brennan’s plurality is that:

“‘local school boards have ‘a substantial legitimate role to play in the determination of school library content’ and that districts have ‘significant discretion’ to determine the books available in school libraries.” School boards, however, cannot remove books “simply because they dislike the ideas in the books”. But, books can be removed according to Pico, based on “‘educational suitability’ or if the books are ‘pervasively vulgar’”, the latter reason agreed to by all the Supreme Court justices.

In the same vein, the Wentzville court held that vulgarity and educational suitability “are at the heart of the determination of the ‘age sensitivity’ determination”; in other words, when books may or may not be age appropriate.

The AASL Standards activity guide for the shared foundation “curate” also recognizes that assessing books in the school library should “be appropriate for the subject area and the age ability level, learning styles, and social, emotional and intellectual development of the students for whom the materials are selected”.

The point is that a book may be removed from the school library without violating students’ rights, nor can the removal of a book honestly be labeled a book ban, ergo, school displays of “banned books” are nothing more than political propaganda.

Using students to advance political advocacy

As TASL says, “students are at the heart of [TASL’s] work, and our purpose is to help them grow academically”. Students are also used to advance the political objectives of the three-tired library organizations.

For example, the School Library Journal is trying to help FIRE (the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression), find student plaintiffs to sue school districts and challenge decisions made regarding books removed from school libraries. FIRE admits to the weakness of the Supreme Court’s decision in Pico and is trying to help get lawsuits filed that might weaken school board authority related to school library book removal.

Students are included in TASL’s advocacy wheel which includes ideas such as helping students form student-led groups. Examples provided include, ProjectLIT, Sustainable Schools, Urban Green Lab, GSA [Gay-Straight Alliance].

A Knox County middle school librarian describes the purpose of a Project LIT book club is to both encourage reading but use the opportunity to “facilitate discussions on diversity, bias, and other relevant social issues.” In this particular book club students whose parents declined consent for the chosen book may not have been aware that the non-consented-to book’s content and themes were still part of the book club’s session.

Similarly aligned to the AASL Standards, a school librarian-supported, student-led banned book club was launched this year at a Georgia high school.

Tennessee law that may impact book challenges

PEN America uses “educational gag order” to characterize state laws which seek to counter the three-tier library association agenda related to advancing the elements of critical race theory, gender diversity and sexualization of students playing out in school libraries.

In 2021, the Tennessee General Assembly passed a law prohibiting the teaching of concepts that derive from critical race theory (T.C.A. 49-6-1019(a)), including for example, that “[a]n individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, is inherently privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or subconsciously”.

And yet, after the law was passed, TASL joined the “Teach Truth” campaign and published a recommended book list which included two books by Ibram X Kendi, one of the most vocal proponents of the elements that comprise critical race theory. It should be of equal concern that TASL has thrown their support to the Zinn Education Project, linked of course to Howard Zinn whose work has come under serious and credible scrutiny.

Public Chapter 1137, passed during the 2022 legislative session requires the Tennessee Textbook Commission to issue guidance for local school districts for reviewing library materials to ensure that the materials are appropriate for the “age and maturity levels of the students accessing the material and that the materials are suitable for, and consistent with, the educational mission of the school”. The Textbook Commission is also authorized to receive an appeal of a local school board’s decision regarding a book challenge.

Public Chapter 1002, also passed during the 2022 legislative session ensures that Tennessee’s “harmful to minors” obscenity law applies to digital and other online resources provided to students. It is important to note that the law removed the education exception that blocked the obscenity law from applying to materials in schools.

Public Chapter 744 dubbed the “Age-Appropriate Materials Act”, requires each public school to maintain and post on the school’s website a list of the materials in the school’s library collection. It also requires each local board of education to adopt a policy to establish procedures for the review of school library collections.

Conclusion

Using its library standards, the AASL which describes school librarians as “change agents”, has issued a charge to school librarians to wage a social justice campaign, create student activists, collaborate with educators in their school buildings and use the AASL standards to influence them.

TASL has adopted these standards and is using the standards to train school librarians. AASL and TASL suggest that school librarians should have the power to be the sole and independent determiners of what books reside in a school’s library and which ideas and books our children should be interested in and read.

School displays claiming that selected books have been “banned” mislead students, teachers and visitors to the school. The displays undermine the value parents and legal guardians bring to a student’s learning, the same parents and legal guardians who educators say they want involved in a child’s education.

Some might argue that pushing the idea of “banned books” invites acrimony between students and their parents and guardians, or undeserved distrust of elected officials. Displays that encourage students to inappropriately “act like a rebel” use the school library for a political agenda that is not really about “freedom to read” but rather, a protest against compliance with constitutionally sound state laws.